Understanding breast structure and developmental processes is pivotal for surgical and diagnostic approaches. This article explores embryological stages and pubertal transformations, revealing their implications for congenital anomalies and normal functions.

It covers embryology from fetal formation to puberty's hormonal changes and details breast anatomy, including glandular components, vascular and lymphatic systems, and supportive connective tissues. These insights are crucial for medical professionals to enhance clinical practice and accurately assess developmental stages and anatomical variations, which are vital for effective patient care.

Embryology of the Breast

The embryological development of the breast is a complex process that begins in the fetus and continues through puberty. This development is crucial for understanding various congenital abnormalities and the anatomical basis of breast-related procedures.

- Origin and Initial Development: The breast derives from the ectoderm and begins developing as a small thoracic portion of tissue that penetrates the underlying mesenchyme during the fourth week of gestation.

- Mammary Ridge Formation: By the sixth week, the mammary (milk) ridge develops, extending from the axilla to the groin, although most of this ridge involutes except at the site of the breasts.

- Bud Differentiation: Between the eighth and tenth weeks, breast growth starts with the differentiation of cutaneous epithelium in the pectoral region. The primary bud emerges, giving rise to secondary buds that develop into lactiferous ducts akin to modified sweat glands.

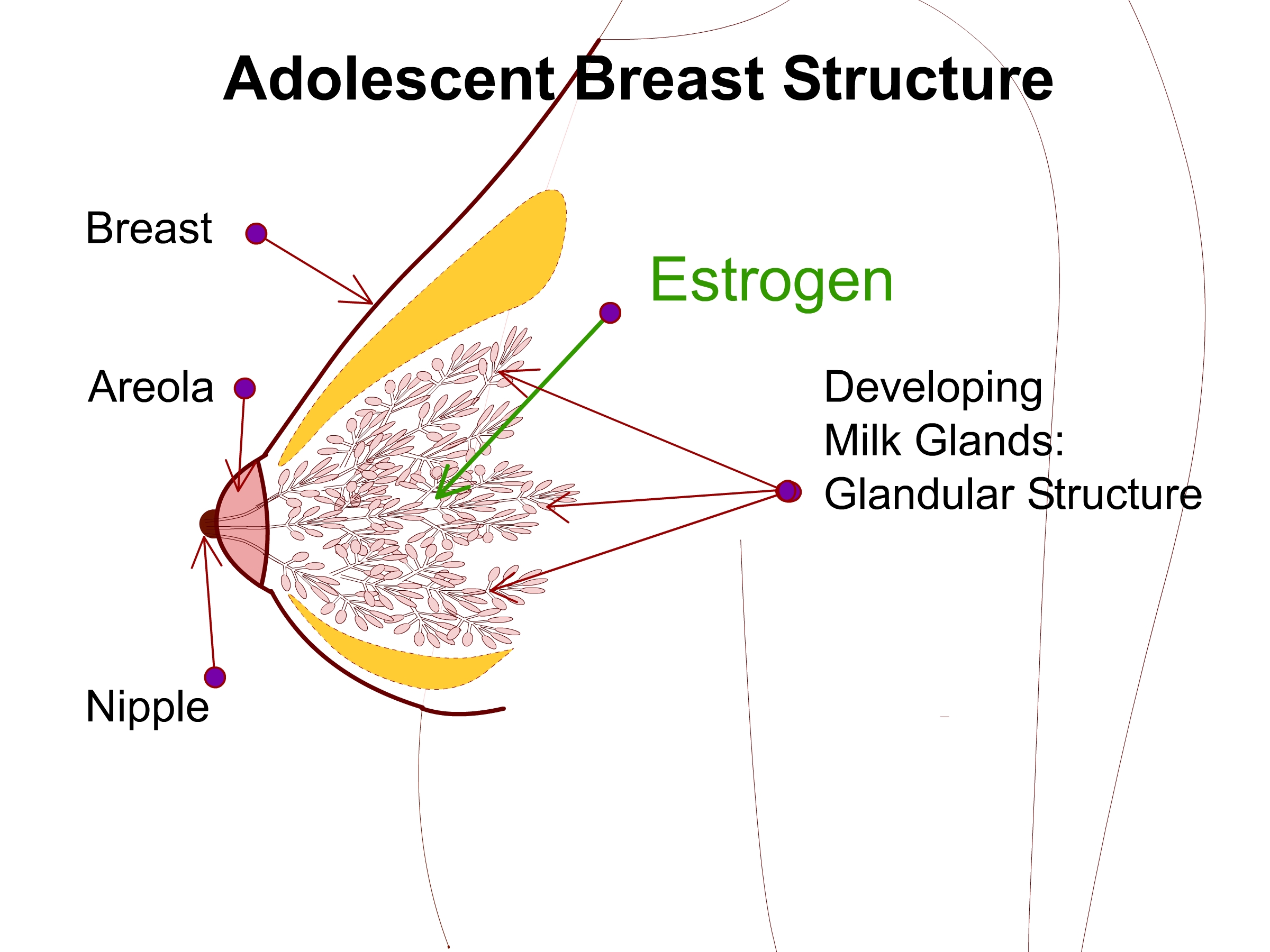

- Sexual Dimorphism: The basic structure of the breast is similar in both sexes until puberty. Hormones, especially estrogen and progesterone, drive further development in females, leading to the formation of glandular tissue.

- Nipple and Areola Development: By the fifth month, areolae begin to form. The nipple develops due to the proliferation of mesenchymal cells and thinning of the overlying epidermis. Towards the end of fetal development, acini develop around the tips of the lactiferous ducts, forming the mammary pit.

- Congenital Anomalies: Supernumerary breasts (polymastia) and nipples (polythelia) can occur anywhere along the milk ridge, with the most common location for polymastia and polythelia being the left chest wall, below the inframammary crease. Polythelia is the most common congenital breast anomaly, occurring in about 2% of the population.

- Postnatal Changes: After birth, the breasts remain relatively undeveloped until hormonal changes at puberty induce rapid growth and maturation of the glandular components.

Pubertal Development of the Breast

The pubertal development of the breast, or thelarche, marks a key stage in adolescent growth, driven by hormonal interactions initiated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. It involves a series of distinct and clinically relevant stages, classified by Tanner, which are critical for assessing normal and abnormal adolescent development.

- Hormonal Initiation: Puberty typically begins between the ages of 10 and 12. It is initiated by gonadotropin-releasing hormones from the hypothalamus, which stimulate the anterior pituitary to secrete follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).

- Estrogen and Breast Growth:

- FSH stimulates ovarian follicles, leading to estrogen production.

- Estrogens are crucial for the longitudinal growth of the breast ductal epithelium.

- Progesterone, released by the mature corpus luteum, complements estrogen to promote full mammary gland development.

- Anatomical Changes: Development occurs between the superficial and deep layers of the superficial fascia, where Cooper's ligaments provide structural support and connect the two layers to each other and to the underlying musculature.

- Tanner Stages:

- Stage 1: Pre-adolescent; only nipple elevation, no palpable glandular tissue or areolar pigmentation.

- Stage 2: A breast bud forms, and glandular tissue develops in the subareolar area—the nipple and breast project as a single mound.

- Stage 3: Increased glandular tissue; further enlargement of breast and nipple, maintaining a single contour.

- Stage 4: The Areola enlarges, and the nipple forms a secondary mound with increased areolar pigmentation.

- Stage 5: This is the final stage of adolescent breast development; the secondary mound integrates into the overall breast contour, resulting in a smooth contour with no separate projection of the areola and nipple.

- Variability in Development: Genetics, nutrition, and overall health influence individual variations in the timing and progression of breast development.

Breast Anatomy

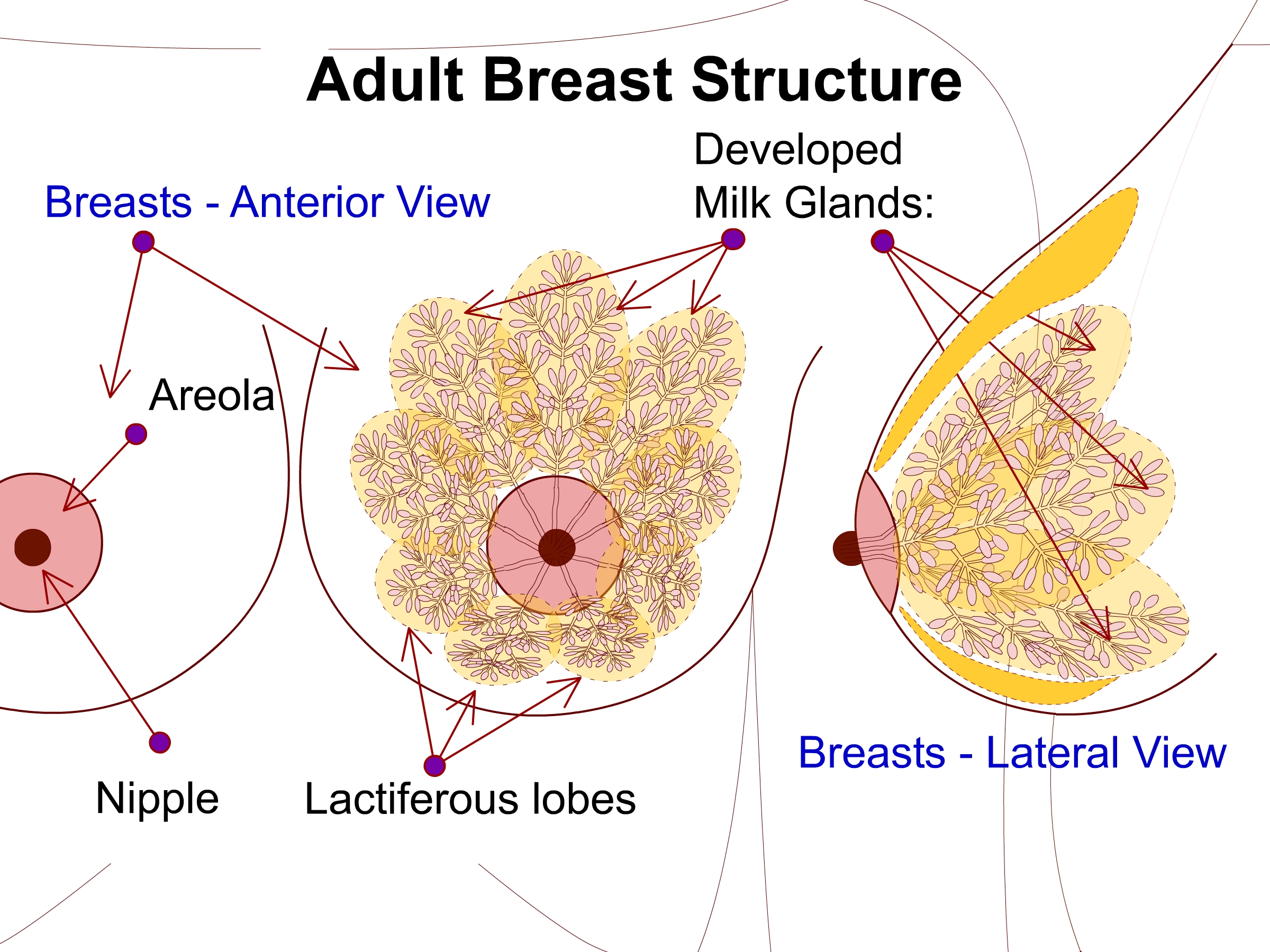

The human breast is a complex structure integral to mammalian physiology, primarily composed of glandular tissue and fat. This anatomical region varies greatly due to factors such as genetics, age, and hormonal status. Its primary function is lactation.

Glandular Structures

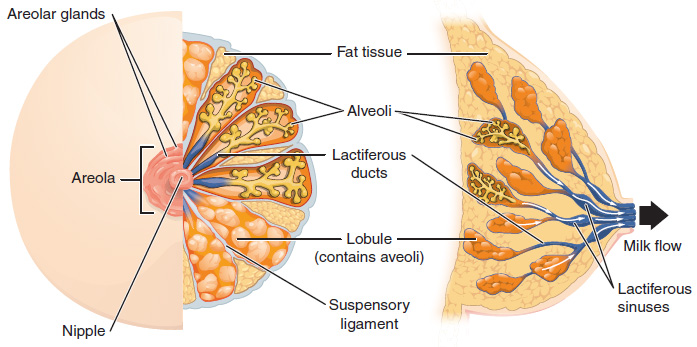

- Lobes and Lobules: The breast contains 15-20 lobes, each divided into smaller lobules where milk is produced. Lobules are situated in a radial distribution, and each contains 10-100 alveoli, which are connected by interlobular ducts to the main lactiferous ducts.

- Ductal System: Lobules drain into smaller ducts that converge into larger ducts leading to the nipple, facilitating milk expulsion. The duct system opens onto the nipple as lactiferous ducts, which may dilate near the nipple, forming lactiferous sinuses that serve as milk reservoirs.

Connective Tissue

- Cooper's Ligaments: Fibrous bands providing structural support by suspending the mammary gland from the chest wall. These penetrate the parenchyma from the dermis, and their attenuation can lead to ptosis.

- Adipose Tissue: Fatty tissue that envelops and protects the lobes and ducts, contributing to the size and shape of the breast. Fat content varies and increases as the glandular component subsides, notably after lactation or during menopause.

Vascular and Lymphatic Systems

- Blood Supply: The breast's vascular supply includes:

- Perforating branches of the internal mammary artery

- Lateral thoracic artery

- Thoracodorsal artery

- Intercostal perforators

- Thoracoacromial artery

- Skin receives blood from a subdermal plexus that communicates with these deeper vessels

- Venous Drainage: Mirrors the arterial supply, predominantly draining to the axilla.

- Lymphatics: Lymph drains into nodes located in the axillary, pectoral, and parasternal regions, which are important for immune function and metastatic pathways.

Nipple and Areola

- Nipple: Contains the terminal duct lobular units and is the milk's exit point, surrounded by smooth muscle fibers aiding in milk expulsion. It has openings for each lactiferous duct and may harbor bacteria.

- Areola: The pigmented area surrounding the nipple contains Montgomery glands, which secrete protective lipids. These glands are large sebaceous glands with milk-secreting potential.

Neurological Components

- Innervation:

- Sensation to the breast is mainly provided by the anterolateral and anteromedial branches of the thoracic intercostal nerves T3-6.

- Supraclavicular nerves from the lower fibers of the cervical plexus (C3, C4) innervate the upper and lateral portions of the breast.

- NAC sensation is derived from the anteromedial and anterolateral branches of the T4 intercostal nerve.

- The intercostobrachial nerve supplies the upper medial arm and can be affected by surgical procedures like axillary dissection.

Additional Structural Features

- Surface Anatomy: The adult breast extends from the second to the seventh rib in the midclavicular line, medially from the sternocostal junction to the midaxillary line laterally. The inframammary fold represents the fusion of the deep and superficial fascia with the dermis.

- Fascial Layers: There are distinct layers of superficial fascia near the dermis and a deep layer on the deep surface of the breast, with a loose areolar plane between this and the deep fascial layer overlying the musculature. The deep fascial layer carries significant importance in the breast's structural integrity and aesthetic appearance.

Lymphatic Drainage of the Breast

The lymphatic drainage of the breast is critical for immune surveillance and the pathophysiology of breast cancer metastasis. It involves a complex network of superficial and deep lymph nodes and vessels that drain lymphatic fluid from the breast tissues.

- Superficial Drainage: Originates from a periareolar lymphatic plexus that accompanies venous drainage, involving the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

- Deep Lymphatic Drainage: This begins with individual lymphatic channels draining each lactiferous duct and lobule, penetrating through the deep fascia of the underlying musculature.

- Axillary Nodes: The primary route of lymphatic drainage from the breast, with several levels:

- Level I: Located lateral to the lateral border of the pectoralis minor muscle.

- Level II: Found behind the pectoralis minor and below the axillary vein.

- Level III: Positioned medial to the medial border of the pectoralis minor.

- Central and Apical Nodes: Lymph from the breast travels to the central axillary nodes, then to the apical axillary nodes, and potentially to the supraclavicular nodes.

- Internal Mammary Nodes: These nodes receive lymph from the medial aspects of the breast and are located along the internal mammary artery, particularly draining along internal mammary perforating vessels.

- Pectoral (Anterior) Nodes: These are situated along the lateral edge of the pectoralis major muscle and drain the anterior breast.

- Subscapular (Posterior) Nodes: Positioned along the scapular region, involved in the drainage of the posterior aspect of the breast, and receiving lymph from the upper outer quadrant.

- Interpectoral Nodes (Rotter's Nodes): Found between the pectoralis major and minor muscles, these nodes are critical in the pathway, though less commonly involved.

- Parasternal Nodes: Medial lymphatic channels follow the internal mammary perforating vessels to drain into these nodes.

- Supraclavicular Nodes: Involved in the final stage of lymphatic drainage, where lymph from the breast may ultimately drain before entering the venous system.

Bra Sizing Overview

Bra sizing is essential for ensuring comfort and support. It utilizes a combination of band size and cup size determined by specific measurements. Accurate sizing is critical for both aesthetic appearance and physical health, although it is acknowledged that sizes can vary significantly between countries and manufacturers.

- Band Size: Measured in inches around the torso directly under the breasts at the inframammary fold (IMF). To determine band size:

- Add 4 or 5 inches to this measurement to reach an even number in the United Kingdom.

- Band sizes typically range from 28 to 46 inches.

- Cup Size: Determined by the difference between the circumference of the bust at its fullest point and the band size measurement:

- <1 inch difference – AA cup

- 1 inch difference – A cup

- 2 inches – B cup

- 3 inches – C cup

- 4 inches – D cup

- 5 inches – DD cup.

- Each inch of difference represents a one-cup size increase.

- Measurement Technique:

- Ensure the measuring tape is level and firm around the torso for the band size.

- Measure the bust at the fullest point without compressing the breast tissue to determine cup size.

- Fitting Considerations:

- The bra band should be snug but comfortable, able to fit two fingers under the band but not loose enough to pull away from the body.

- Bra cups should fully encase the breast tissue without spilling over or leaving empty space in the cup.

- Adjustments: Bra straps should be adjusted to prevent slipping and to lift the bust line effectively without causing discomfort or indentation on the shoulders.

- Common Issues: Incorrect bra size can lead to discomfort, poor posture, and even physical symptoms like back pain. Frequent reassessment of bra size is recommended due to natural changes in body size and shape.

Courses are

coming soon...

Our aim is to comprehensively cover every specialty within medicine, bringing you courses that provide value and aid your professional growth.